The term “proletariat” has largely pejorative connotations, which is all too understandable in view of its meaning.

The fact that the inequality between women and men is also very high with regard to an academic career cannot be dismissed.

Accordingly, it is not surprising that in 2013 there was a high discrepancy between the proportion of male (35,426) and female (9,587) full-time professors at German universities. But how does such a discrepancy come about? Are women simply not ambitious enough? – Of course not.

The academic career – a courageous path

As a woman, embarking on an academic career is usually quite brave. In addition to the pressure to demonstrate excellent academic performance, to work day and night in the lab on research projects, and to fulfill one’s teaching duties on the side, women have to contend above all with prejudice and bullying. Their qualifications are constantly questioned, their achievements insufficiently rewarded, and their willingness to devote themselves heart and soul to the fields of scientific research doubted. No wonder that the term “academic proletariat” is increasingly associated with young female scientists. The term stands for inequality, oppression and injustice. The reasons why more and more young female academics find themselves in such a position are easy to name:

-

There are too few role models

Who should a young female scientist look to for guidance when she is discouraged by words such as “Oh dear, if you go down this path, it will be very arduous” and corresponding statistics showing the low percentage of female professors in academia?

Who should a young female scientist look to for guidance when she is discouraged by words such as “Oh dear, if you go down this path, it will be very arduous” and corresponding statistics showing the low percentage of female professors in academia?

More visibility needs to be created so that female professors can encourage young women through reports and interviews and encourage them not to rule out an academic career for themselves. Usually, it is not only “envious people” who want to advise you against a scientific career. Even non-academics or family members often discourage one from pursuing a career in higher education because they think they know one best and can’t imagine that the person might later have children, marry, and become “domestic.”

-

The higher education system is not sufficiently attuned to young female scientists

Temporary contracts, employment as a “lecturer for special tasks” and working conditions that are not very family-friendly are just some of the criteria that make it very difficult for women to combine a family and an academic career. Of course, you can’t teach in the morning, correct protocols, term papers, and term papers in the afternoon, and still devote yourself to your research work in the evening when you have a child at home who demands attention, a household that needs to be run, and a partner who wants support in his or her own professional development. At this point, the university must counteract the previously continued trend of the “steadfast superwoman” in order to provide these women with relief.

In this category, of course, the scope of action of female and male scientists is rather small, because the regulation of internal university equality measures undoubtedly falls to the university itself. Fixed-term contracts, family care times, flexible working hours, home office (at least during times when teaching is not actively required) or an increase in the participation of women, for example in recruitment procedures, are just some of the measures that could be taken to improve equal opportunities for women and men at German universities.

-

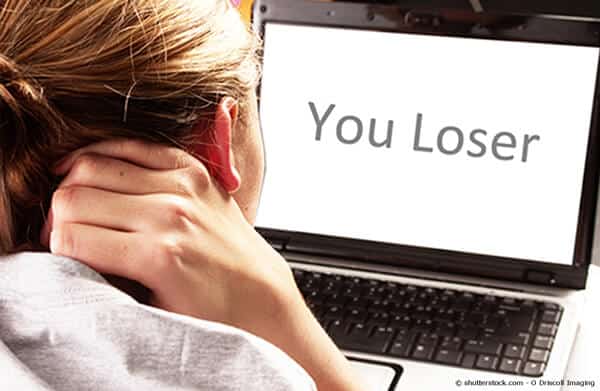

Bullying at universities is not taken seriously enough

Of course, there are mentoring programs, in which one is cared for and advised by trained personnel of the university in case of psychological and physical problems. However, the topic of “bullying” is usually not addressed, and even statistics often only include young people up to the age of 24, or adults who have been asked about bullying in the workplace.

Of course, there are mentoring programs, in which one is cared for and advised by trained personnel of the university in case of psychological and physical problems. However, the topic of “bullying” is usually not addressed, and even statistics often only include young people up to the age of 24, or adults who have been asked about bullying in the workplace.

That mobbing is an insidious process and is not uncommon at universities will be confirmed by many young female (and male) scientists.

Statements such as “You’re Professor XY’s favorite anyway” or “We both know how you got this position” are just two of countless examples of how bullying can manifest itself at universities.

Preventive action must be taken here, not just when bullying is already taking place, because then the inhibition threshold is often too high to (justifiably) incriminate a superior. Universities in Germany have many, very good programs (see also nexus impulse aus der Praxis, Issue 3, July 2013) to promote integration and tolerance; accordingly, they should also show more willingness to act in the area of bullying.

-

Your role as a woman will be your undoing

That we tend to often categorize other people into certain stereotypes is undeniable. The associated prejudices and expectations are increasingly becoming a career brake, especially for women. “You want to be a professor? How are you going to do that with the children? Think about your biological clock, and after all, they have to be taken care of, otherwise you won’t have a bond with their mother.” “What about your husband’s professional success? You can’t ask him to take a back seat there, he could have a great career” etc. etc.

The bad conscience

Often women who aspire to a career in science are plagued by a guilty conscience, but this would be unnecessary if there weren’t enough people to talk you into it.

- Of course you can have your children later

– Planning is the key here.

The mother’s bond is of course a lame excuse, because this also exists when the child is cared for during the day by a childminder or in a daycare center. - Take the freedom to have a career, because you don’t get a second life to make up for it.

- Find a good solution with your partner, because a stable relationship consists of a good mix of give and take.

If the partner cannot also take a step back professionally, this does not immediately mean that you have to give up your path and your goal. Strong and good communication serve as key factors here for mutual satisfaction.

Your opinion is important to me

During our mentoring sessions, as well as in everyday university life, I repeatedly meet fellow students who tell me about their careers and also about the problems they encounter along the way. Discrimination, bullying, and lack of recognition are just a few of the issues these young female undergraduate and graduate students address, indicating the stress they experience during their studies and doctoral years.

I have tried to point out in this blog post that it is not the young women scientists themselves who can be held accountable for leaving their careers prematurely or not completing them with sufficient success. Many factors play a crucial role here and must be taken into account when evaluating academic careers.

I personally would be interested in this of course

Are there any other factors that one may encounter as obstacles on the scientific career path and if so, how did you deal with them? What experiences might you have had with the above issues such as bullying or prejudice?

I would be happy if you share your experiences with me so that we can broaden our horizons through a common exchange of opinions.

About the author

Kinga Bartczak advises, coaches and writes on female empowerment, new work culture, organizational development, systemic coaching and personal branding. She is also the managing director of UnternehmerRebellen GmbH and publisher of the FemalExperts magazine .